Union Berlin are a club that defies not just the odds but, at times, even logic itself. While illustrious, free-spending Hertha have floundered, their more industrious, more provincial, more modest neighbours from the East are continually punching above their weight and enjoying a real fairytale season. Despite a slump before the World Cup break where it seemed as though their logic-defying Expected Goals numbers – some of the lowest in the league – had finally caught up with them, Union are now once again enjoying their place in the sun near the top of the Bundesliga and having just knocked Dutch giants Ajax out of the Europa League.

It is, however, not just in their underlying numbers where they are outliers. Their recruitment, too, is an area where Union raise eyebrows because it seems to be at odds with what you would normally expect from a club that is steadily improving. Conventional wisdom has it that one of the most effective ways for a football club to develop – at least in terms of on-pitch performances – is through stability and continuity: gradually augmenting a team by weeding out the old and unproductive and plucking in higher-level performers bit by bit – rather than radically overhauling the squad every season – is a surefire way to evolve and keep things fresh without forfeiting team chemistry. Yet Eisern Union are doing things slightly differently.

To be sure, stability is key in East Berlin, too, just not when it comes to their playing personnel. In fact, since arriving in the Bundesliga in 2019, the side from picturesque Köpenick has made a habit of being a busy bee in the transfer market, with scores of players arriving and departing every year (13 players have been signed this season alone). One example must suffice to illustrate this. Comparing the side that beat RB Leipzig 2-1 on February 11 with one from almost exactly a year earlier – in this case a 3-0 loss to Dortmund on February 13, 2022 – illuminates the transience and fluidity of Union’s roster-building: only two players, penalty-taking centre-back Robin Knoche and crucial forward Sheraldo Becker, started both games, and out of the 20 players that made the matchday squad against Dortmund, nine have since left the club.

So what, then, is Union’s secret? Simply put, their management, from head coach Urs Fischer up to sporting director Oliver Ruhnert, and indeed all the way up to the highest echelons of the club where their not-always-uncontroversial but canny president Dirk Zingler employs a very hands-on approach in conducting things. And it is here where a combination of continuity, adaptiveness and a clear division of labour yields high rewards. Zingler has been presiding over club developments for two decades, while Ruhnert joined in 2017 (initially as head scout). It was the latter who, after his change in roles, brought Urs Fischer to the club and who is largely behind Union’s erratic recruitment with its eye-catching volume of player turnover.

The fact that Union’s playing squad is seemingly always in flux is, however, not by design. On the contrary, when asked about the ever-changing roster, Fischer lamented that exogenous circumstances force Union to repeatedly dip into the market every summer. “Integrating 12, 13, 14 players,” he told Neue Zürcher Zeitung in early February, “into a functioning [system] is a challenge.” But, he added defiantly, “these challenges keep us on our toes.” It is about how you respond to the obstacles that the turbulent football business puts in your way that determines the fate of your club.

Here, communication is just as important as market insight. Fischer is constantly in dialogue with Ruhnert, so the latter is intimately familiar with the former’s system and knows exactly what type of player to target. “We obviously don’t talk about football just once a week,” explains the 57-year-old head coach. “We discuss the game daily, including with sporting director Ruhnert. He, of course, also recognizes what kind of players we already have and what we could use more of. Does the player fit in terms of profile, does he fit character-wise, is he prepared to put himself in the power of the team?”

It is, however, also a reciprocal relationship: when Ruhnert signed the excentric Max Kruse, Fischer proved his tactical mettle by being able to adjust his usually so rigid system in order to accommodate the free-spirited attacker. And he did so with incredible success: Kruse proved instrumental to Union’s first-ever qualification for European competition. Yet the cooperation with Kruse, as with many players recently, was ultimately only short-lived, and he departed for Wolfsburg after just 18 months.

But with a capable man like Ruhnert in charge of the recruitment department, Union are rarely fazed by that, and they have been able to cope with every exit since getting promoted. When Kruse left, Taiwo Awoniyi stepped up and even bettered his erstwhile teammate’s goalscoring tally; and when he, too, moved on prior to this season, Sheraldo Becker suddenly became Union’s marquee threat. Genki Haraguchi arrived in the summer of 2021, became an integral part of Fischer’s midfield, and then departed again this January. Rather than panic after losing a vital cog mid-season, Union already had a competent replacement lined up in Aïssa Laïdouni, and they haven’t missed a beat without Haraguchi. The ability to rapidly adapt to constantly changing circumstances is what sets Union apart from many sides.

It is self-evident, though, that no club, much less one that is continually wheeling and dealing, can attain a 100 per cent hit rate on transfers. The challenge of integrating players that Fischer alluded to can often prove insurmountable, which in turn perpetuates this ostensibly vicious cycle of constant personnel turnover: some players just don’t work out, and if you sign a lot of players, the names that didn’t fit the system are bound to accumulate. Therefore, it’s not massively surprising that Union’s recruitment has seen a lot of trial and error over the years.

But they can afford to miss on some signings. For Union know their financial limitations. They won’t break the bank on someone if they are not absolutely certain that they will fit the system and improve it; in fact, they rarely ever break the bank in the first place, making excellent use of free transfers and loan deals. In the Leipzig game, the most expensive Union player on the pitch was recent arrival Josip Juranović, who set the Köpenick side back some €8.5m, making the right-back their most-expensive acquisition ever. With a record signing that cost less than nine million euros, they are keeping pace with Bayern and Dortmund!

For every Keita Endo, there is a Sheraldo Becker, for every Rick van Drongelen, there is a Robin Knoche, for every Leon Dajaku or Marcus Ingvartsen, there is a Taiwo Awoniyi or a Jordan. In other words, when Union get a player who doesn’t fit Fischer’s system or who fails to acclimatize to life in East Berlin, he doesn’t leave a noticeable negative mark on the team or a dent in the club’s finances. Because there is always someone waiting in the wings ready to step up – a testament to Fischer’s coaching – or someone getting flipped for a sizeable profit – a testament to Ruhnert’s business acumen. Awoniyi, brought in for a similar fee to Juranović, was sold for €20.5m, Sebastian Andersson, originally a free transfer, left for €6.5m and even a 33-year-old Max Kruse flushed some €5m into the club’s coffers. Union might miss occasionally, but when they hit, they hit big time.

Perhaps more instructive to showcase Union’s expertly operating organization and way of conducting business is a recent episode involving a failed transfer. The news that Ruhnert was negotiating with the representatives of former Real Madrid man Isco made waves in Germany, so much so that even the Union players were joking about the move in training and on social media. A signing like this would have cemented Union’s status as a nouveau big hitter of German football. But when the Spaniard’s cortège demanded more than had initially been agreed upon in the preliminary stages of the negotiations, Ruhnert had no qualms about pulling out of the deal.

While it caused some disappointment among the more starry-eyed Union supporters, this was probably for the better. Unlike some fans, the astute sporting director was not blinded by the allure of a five-time Champions League winner and was not prepared to put his club’s wage structure and long-term stability at the mercy of a hit-and-miss “luxury player” who is not a natural fit for Fischer’s system.

The talks with Isco naturally evoked fond memories of the heady Kruse days, but Ruhnert realised that the circumstances now called for a more conservative approach: on a personal level there would have been questions over how well Isco would adapt to life in Germany, but more important on a sporting level is the simple fact that the Spaniard is a different type of player to the German; it may be easier for a team to make defensive concessions to accommodate a forward like Kruse, but Union could ill afford to do the same in midfield where their ever-reliable grafters play such a vital part in making their defensive bulwark one of the most unassailable in the league.

Fischer was quick to remind people that there are always risks attached to high-profile signings: “Our strength is the team, the collective. We don’t have difference-makers like Bayern Munich . . . But let’s take Max Kruse – Max offered the side entirely new ways of playing. Isco could perhaps have done the same, but you never know beforehand if things will work out.” In this instance, they were not prepared to take the risk. And it is this which ultimately defines Union. Theirs is a low-risk, high-reward approach.

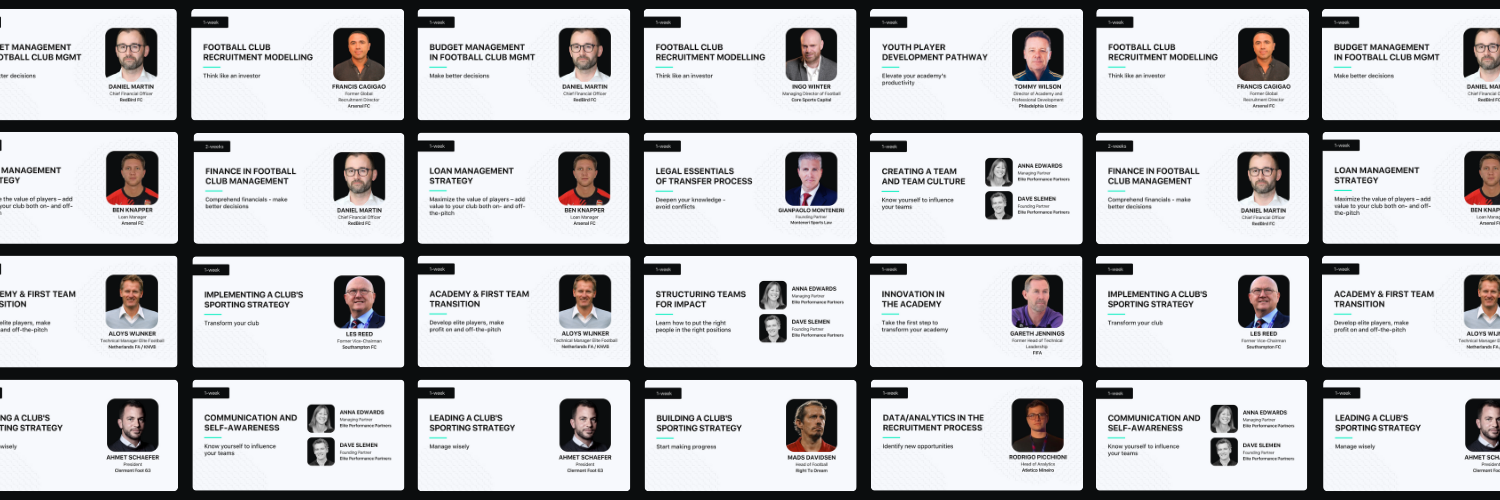

Some trends are noticeable when analyzing Union Berlin’s recruitment under the Fischer-Ruhnert regime:

- they buy cheap and sell (relatively) high (the top six sales in the Ruhnert era are Awoniyi, Andrich, Andersson, Friedrich, Ryerson, Kruse – combined outlay: €14.3m/income: €49m = profit: €34.7m)

- they scout lower divisions/smaller markets (2. Bundesliga, EFL Championship/Switzerland, Hungary, Poland, Scotland) where transfer values aren’t as inflated as in the top five leagues

- the low-risk approach is nicely illustrated by their effective use of free transfers (Kruse, Doekhi, Khedira, Haraguchi, Knoche, Gießelmann, Luthe) and loans (Leite, Baumgartl, Awoniyi, N. and K. Schlotterbeck, Bülter)

- they mostly target players in their prime but are not averse to veering to either end of the spectrum (veterans: Michel, Gentner, Subotić, Kruse, Luthe/youth: N. Schlotterbeck, Schäfer, Leweling, Jaeckel)

- they rarely sign wholly inexperienced players; the above-mentioned youngsters arrived in their 20s and with considerable first-team experience already under their belts

- the goal is to build a cohesive unit where the individual is subsumed under the collective; personality and discipline are important factors in the scouting process

In conclusion, Union Berlin are not just a well-oiled machine on the pitch thanks to the firm and proficient guidance of Urs Fischer, they are also a smartly run business under the auspices of Dirk Zingler and Oliver Ruhnert that is focused on the concrete reality of the here and now, rather than some idealistic future that may never come to pass. They are pragmatic in their recruitment, chiefly acquiring players that can contribute to the team immediately (January signings Josip Juranović, Jérôme Roussillon and Aïssa Laïdouni already look like established members of the side).

The secret to Union’s success is that they neither mortgage the club’s fate on big names and individual performers nor are they bedazzled by the enchanting prospects of future profits that an overt emphasis on youth development promises. The latter, such a potentially lucrative source of income, should not be neglected altogether, however, and it’s certainly an area where Union could still improve in order to further diversify their sources of revenue. As of right now, though, Union have struck the right balance in terms of recruitment, and it is yielding incredible results.

The recruitment feeds into the club culture, but the club culture also informs the recruitment. Everything from Urs Fischer’s defensively stout, “anti-gegenpress” style to the explicit emphasis on the disciplined collective is tailored to, and an expression of, the down-to-earth nature of the club and the community surrounding it, in which it is so deeply rooted. Thanks to masterful management, Union boast a potent mixture of unmistakable, self-perpetuating identity and a perfectly attuned team that has allowed the club to rise from the second division to the top of the Bundesliga in the space of merely four years.